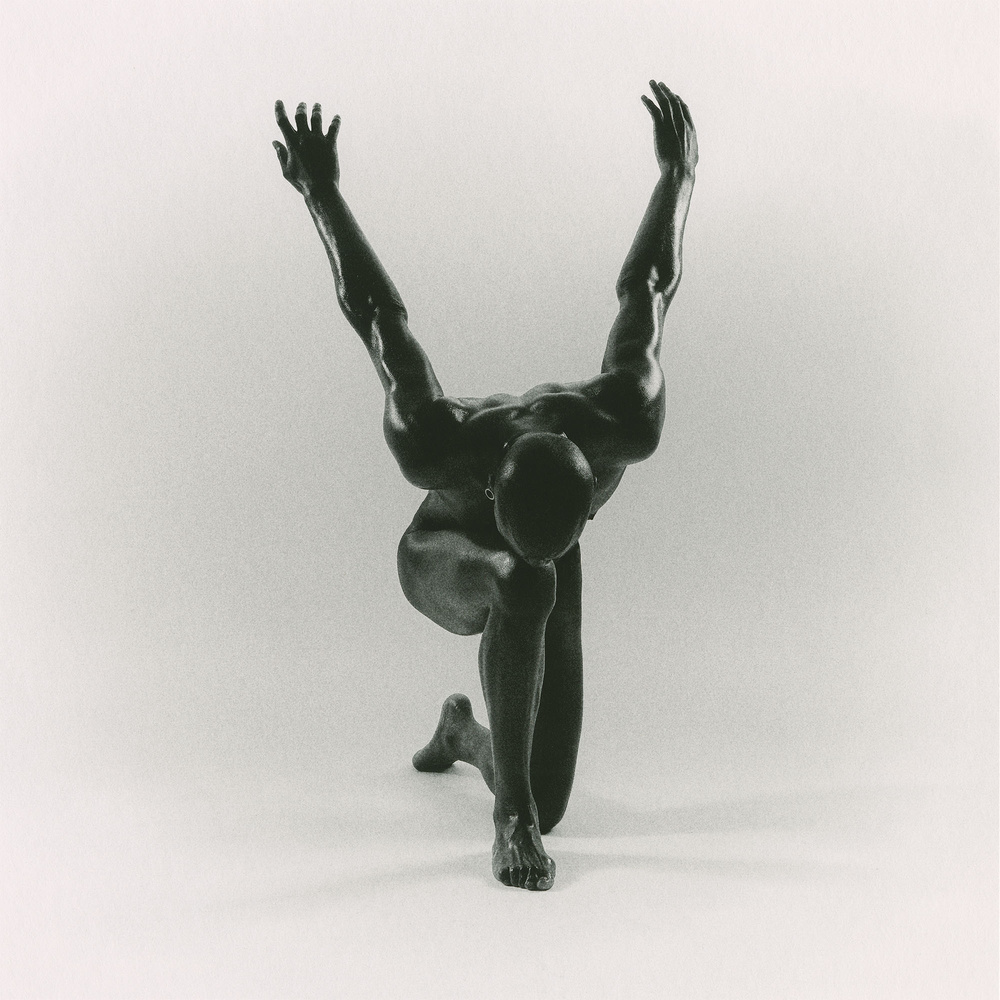

Petite Noir transcends borders — physical and musical — in pursuit of artistic vision

By Fred Love

Editor’s Note: This article was written to promote a July 21 concert Petite Noir had been scheduled to perform at xBk Live. That concert and accompanying tour were canceled due to factors beyond xBk’s control. We at xBk still wish to promote the artist to our community and have edited the following story to reflect the concert cancellation. We hope to host Petite Noir at a later date.

Yannick Diekeno Ilunga refuses to allow borders to define him and his sound.

The international artist known as Petite Noir defies genre, blending rock, pop, electronic, punk, folk, and traditional African music into a singular, boundary-breaking sound. Just as his multicultural heritage spans Congolese, South African and European roots, his music resists categorization at every turn.

“There’s a no-boundaries approach to my music,” Ilunga said in a recent interview from Cape Town, South Africa. “That’s how I live. That’s how I grew up.”

Born in Belgium to Congolese parents, Ilunga spent much of his youth in South Africa and now splits his time between Brussels and Cape Town. Along the way, he’s developed strong artistic ties in Paris and London. Every mile he’s traveled, and every new city he explores, adds new textural possibilities to his musical landscape.

His refusal to adhere to the conventions of any single genre often draws resistance from critics and members of the music industry who try to foist upon him their preconceived notions of how music should be written and performed, especially music produced by a Black man.

He doesn’t allow that criticism to slow his fierce pursuit of his artistic vision.

“I’m constantly challenged and projected on,” he said. “I’ve come to realize that a lot of the time, people judge you at the level they are on. And most times, it comes from people who’ve never been anywhere close to where you want to go.”

That tension between expectation and exploration fuels Petite Noir’s work. On stage, he performs in a power trio — joined by a drummer and guitarist while handling bass duties himself. He promises a dynamic, sometimes unpredictable performance.

“I love the idea of being kind of messy,” he said. “I hate when music sounds very clean, especially live. I love the energy and rawness of music being almost tangible.”

Petite Noir’s sonic philosophy is encapsulated in a term he’s embraced: Noirwave — a genre-fluid fusion of post-punk, metal, Afrobeat, electronic, indie rock, and traditional Congolese rhythms. It’s a sound that’s both deeply personal and culturally expansive.

“My background is multicultural, and I really put that into the music,” Ilunga said. “The music is way harder and punkier than you might expect, but it also includes ancestral and traditional sounds.”

That same borderless ethos carries through to his lyrics, which often explore identity, heritage, and shared human experience. His lyrics attempt to tear down the artificial and often arbitrary barriers that separate human beings, blending personal and cultural themes that usher the listener into the narratives. The emphasis on common emotion and experience can have a unifying effect on the audience. His most recent full-length album, MotherFather (2023), weaves these themes into lush, layered production.

The track “Blurry” from MotherFather showcases Ilunga’s long-held fascination with distorted sounds. The song’s strummed guitar, which forms the rhythmic backbone of the first half of the track, is filtered through warped electronic textures, while booming percussion enters the mix later to root the song in hip-hop and industrial sounds. Earlier releases like 2015’s La Vie Est Belle / Life Is Beautiful and The King of Anxiety EP introduced his genre-smashing approach to an international audience.

He’s also quick to cite influences that defy expectations. His early musical loves were metal and hardcore. He shouted out Slipknot, calling the Des Moines metal legends a formative influence that sparked his fascination with distortion and heavy production.

“Genres are like languages sometimes,” Ilunga said. “We can use things from one family of sounds and add our own. The destruction and chaos of metal can work well with the tones of traditional African music. That makes sense to me.”

And that’s Petite Noir’s goal: to move beyond traditional borders — cultural, sonic, and emotional — and into unexplored territory.